-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Annamary Rugakiza Stanislaus* and Husna Twalib Msangi

Corresponding Author: Annamary Rugakiza Stanislaus, Department of Ophthalmology, Temeke Regional Referral Hospital, P.O. Box 45232, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Received: November 1, 2025 ; Revised: November 03, 2025 ; Accepted: November 05, 2025 ; Available Online: November 07, 2025

Citation: Stanislaus AR & Msangi HT. (2025) Glaucoma in Tanzania: A Systematic Review of Current Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. J Clin Ophthalmol Optom Res, 3(1): 1-6.

Copyrights: ©2025 Stanislaus AR & Msangi HT. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

Background: Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide and presents a disproportionate burden in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Tanzania, population surveys and hospital records reveal consistently late presentation, extremely low awareness, and poor treatment adherence. These systemic gaps perpetuate preventable blindness despite the availability of effective interventions.

Objective: To synthesize current evidence on the epidemiology, awareness, clinical presentation, and management of glaucoma in Tanzania, while highlighting persistent barriers and mapping future directions.

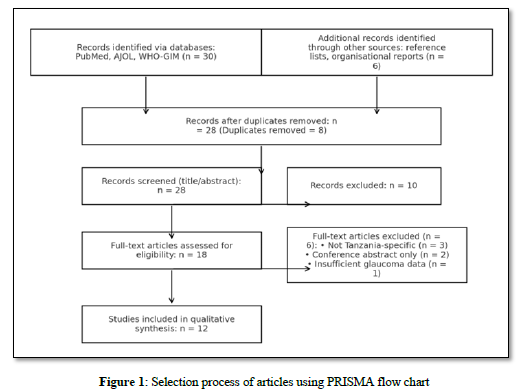

Methods: A systematic search of PubMed, African Journals Online, WHO Global Index Medicus, and Google Scholar was conducted up to September 2025, following PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Studies were included if they reported on prevalence, awareness, clinical features, or management of glaucoma in Tanzania. Two reviewers independently screened, extracted, and appraised data.

Results: Out of 36 records identified, 12 met eligibility criteria. Population-based surveys reported prevalence between 3–5% among adults ≥40 years, with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) as the dominant subtype. Awareness was low (<15%), and over 70% of patients presented with advanced visual field loss. Identified barriers included high treatment costs (reported in 5 studies), limited ophthalmology workforce (4 studies), inadequate diagnostic capacity (3 studies), and fragmented referral systems (2 studies). A randomized trial demonstrated selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) achieved treatment success in 61% of eyes at 12 months, offering a feasible alternative to topical therapy. Pediatric studies highlighted delayed referral and poor follow-up, with >80% presenting with low vision at baseline.

Conclusion: Glaucoma in Tanzania remains a silent epidemic marked by late detection, poor awareness, and limited access to affordable treatment. A national glaucoma control strategy that integrates awareness campaigns, task-shifting for screening, subsidized treatment models, and strengthened referral pathways is urgently needed to curb irreversible blindness.

Keywords: glaucoma; Tanzania; blindness; late presentation; awareness; treatment gaps; primary open-angle glaucoma; sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, affecting an estimated 80 million people in 2020, a figure projected to rise to over 111 million by 2040 due to population ageing and growth [1]. Unlike cataract, the visual loss from glaucoma is permanent, making early detection and effective management essential for preserving vision and quality of life. Sub-Saharan Africa bears a disproportionate burden, with the highest prevalence of blindness from glaucoma relative to other world regions [2]. The challenge is compounded by weak health systems, low awareness, and socioeconomic barriers that delay access to diagnosis and care [3].

In Tanzania, glaucoma has been recognized as a major cause of blindness in both community and facility-based studies. A landmark population survey in Kongwa district reported a prevalence of 4.16% among adults aged 40 years and older, with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) accounting for most cases [4]. More recent hospital-based studies from Dar es Salaam and Moshi have consistently documented that patients present very late, often with advanced visual field loss or blindness at their first visit [5,6]. For example, nearly 30% of newly diagnosed patients in tertiary eye units were already blind in at least one eye [5]. Compared to European cohorts, Tanzanian patients are almost ten times more likely to present with severe glaucoma at diagnosis [7].

Awareness of glaucoma among the general population is strikingly low, with less than 15% of affected individuals having any prior knowledge of the disease before their diagnosis [8].

Cultural perceptions, lack of routine eye checks, and reliance on traditional healers contribute to delays in seeking care [9]. Access to treatment also remains a major barrier. Medical therapy with topical intraocular pressure–lowering drugs dominates practice, but adherence is poor due to high costs, limited availability, and the requirement for lifelong daily use [10]. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) has emerged as an effective alternative in randomized trials conducted in Tanzania, but its adoption is still limited outside specialist centers [11]. Pediatric glaucoma presents additional challenges, with most children referred late and experiencing irreversible visual impairment at baseline [12].

Given these realities, glaucoma in Tanzania represents a silent epidemic—under-recognized, poorly prioritized in health policy, and inadequately resourced in terms of prevention and treatment. This systematic review aims to synthesize existing evidence on glaucoma prevalence, awareness, presentation, and treatment in Tanzania, while highlighting the systemic challenges and outlining future directions for national glaucoma control strategies.

METHODOLOGY

Protocol and Guidelines

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement [13]

Search Strategy

We systematically searched PubMed/MEDLINE, African Journals Online (AJOL), WHO Global Index Medicus (GIM), and Google Scholar up to September 1, 2025. The search combined MeSH and free-text terms: “glaucoma” OR “primary open-angle glaucoma” OR “ocular hypertension” AND “Tanzania”. No language restrictions were applied, though all identified articles were in English. To supplement database findings, we also hand-searched reference lists of relevant articles and organizational reports (e.g., Tanzanian ophthalmology society reports, WHO Africa regional publications).

Eligibility Criteria

We included studies that Reported on glaucoma prevalence, awareness, clinical features, management, or outcomes in Tanzania, Were observational, interventional, or mixed-methods in design and Were published between 2000 and 2025.

We excluded case reports, conference abstracts without full text, and studies not specific to Tanzania.

Screening and Selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed against inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

Data extracted included: study design, setting, population/sample size, glaucoma subtype, prevalence estimates, awareness levels, stage at presentation, treatment modalities, and key outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools appropriate to each study design.

RESULTS

Study Selection

The database search identified 36 records (30 from PubMed, AJOL, and WHO-GIM; 6 from reference lists and organizational reports). After removing duplicates (n=8), 28 records were screened. Following title and abstract screening, 10 studies were excluded. Of the 18 full-texts assessed, 6 were excluded for not meeting eligibility criteria. Finally, 12 studies were included for synthesis (Figure 1).

Prevalence of Glaucoma in Tanzania

Population-based studies consistently estimate glaucoma prevalence between 3–5% among adults aged ≥40 years. The landmark Kongwa district survey reported an overall prevalence of 4.16%, with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) as the predominant subtype [14]. Subsequent facility-based surveys confirm POAG as the leading form of glaucoma, with higher prevalence in older adults. Community-based surveys also identify glaucoma as one of the top causes of irreversible blindness in northern Tanzania [15].

Awareness and Care-Seeking Behavior

Awareness of glaucoma in Tanzania remains critically low. A qualitative study conducted at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) found that fewer than 15% of patients had prior knowledge of glaucoma before diagnosis [16]. Interviews highlighted financial barriers, lack of routine screening, and misconceptions about eye disease as major contributors to late diagnosis. A population-based study further confirmed that many Tanzanians who became blind from glaucoma had sought care late, often after consulting traditional healers or only when vision loss was advanced [17].

Clinical Presentation

Across multiple hospital-based studies, the majority of patients present with advanced disease. A retrospective review from Dar es Salaam revealed that almost 30% of newly diagnosed patients were already blind in one eye at presentation [18]. Comparative data showed that 44.7% of Tanzanian patients had severe visual field loss at first visit compared with only 4.6% in England, underscoring the magnitude of late detection [19]. Pediatric glaucoma is also marked by delayed presentation: a study of 97 children with primary and secondary congenital glaucoma at KCMC found that over 80% presented with low vision, and follow-up at 2 years was achieved in only one-third [20].

Treatment Patterns and Adherence

Treatment Patterns and Adherence

Topical medications remain the mainstay of glaucoma management in Tanzania, but adherence is low due to high cost (up to 25% of monthly income) and supply inconsistencies [21]. A randomized controlled trial comparing selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) with topical timolol demonstrated that SLT achieved treatment success in 61% of eyes at 12 months compared to 31% with timolol, suggesting a feasible alternative for resource-limited settings [22]. Nevertheless, uptake of SLT remains confined to tertiary centers.

System-Level Challenges

Several systemic barriers exacerbate poor glaucoma outcomes in Tanzania. One major challenge is the limited workforce: ophthalmologists are concentrated in urban areas, leaving rural populations underserved. In addition, diagnostic capacity is constrained. Essential technologies such as visual field testing and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are largely unavailable outside major referral hospitals, restricting early diagnosis and monitoring. The problem is further compounded by fragmented referral systems, where many patients bypass primary and secondary facilities and self-refer late, often when vision loss is already severe [20]. Finally, policy gaps remain evident. Glaucoma has not been adequately integrated into Tanzania’s national eye health strategies, resulting in a lack of prioritization for funding, workforce development, and service delivery [23].

Overall, the findings reveal a consistent and concerning pattern: a high prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) among adults, coupled with extremely low awareness and delayed care-seeking. Most patients present at late stages, often when blindness is already irreversible. Treatment gaps are driven by high costs, limited infrastructure, and poor adherence to long-term therapy. Despite these barriers, there are opportunities for innovation. Scaling up interventions such as selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) and expanding community-based screening programs could substantially reduce the glaucoma burden and improve outcomes across diverse populations.

DISCUSSION

This synthesis underscores that glaucoma in Tanzania remains a major cause of irreversible blindness despite decades of global advocacy for early detection and treatment. The predominance of late presentation mirrors trends across sub-Saharan Africa, where more than half of patients are already visually impaired at diagnosis [15]. Unlike high-income settings where structured screening and widespread availability of diagnostics facilitate earlier detection, Tanzanian patients often encounter systemic barriers—including financial constraints, geographic maldistribution of specialists, and fragmented referral pathways—that delay entry into care. These health system weaknesses suggest that improving outcomes will require more than clinical interventions; it demands structural reforms to ensure equitable access to detection and treatment.

The limited adoption of evidence-based interventions, such as selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT), highlights the need for pragmatic models of care tailored to low-resource settings. SLT has demonstrated favorable outcomes in randomized trials and offers a cost-effective alternative to chronic topical therapy [22]. However, its availability remains restricted to a handful of tertiary facilities, leaving the majority of patients reliant on costly medications with poor adherence. Scaling up SLT in secondary centers, alongside strengthening supply chains for essential eye medicines, could mitigate these treatment gaps. Lessons can be drawn from successful task-sharing models in other chronic diseases, where non-specialist providers were trained to deliver simplified protocols under specialist supervision [16,21].

Policy integration is critical for long-term impact. The absence of glaucoma from Tanzania’s national eye health strategies reflects a missed opportunity for resource mobilization and prioritization [23]. Incorporating glaucoma into broader non-communicable disease frameworks and community-based screening programs could accelerate case detection, particularly in rural populations. Importantly, effective policy must be coupled with community engagement to address persistent misconceptions and promote earlier care-seeking [17,20]. Future research should evaluate implementation models that combine community outreach, affordable technology (such as portable tonometry), and sustainable financing mechanisms. By bridging systemic gaps and embedding glaucoma care within national health priorities, Tanzania can move toward reducing the disproportionate burden of late-stage disease and preventable blindness.

Strengths and Limitations

This review consolidates evidence from both population-based and facility-based studies, offering a comprehensive picture of glaucoma burden and care challenges in Tanzania. By including community surveys alongside hospital data, it captures both epidemiologic prevalence and patient experiences of care-seeking, strengthening the external validity of the synthesis. A further strength lies in its focus on systemic determinants of outcomes—workforce distribution, diagnostic access, and policy integration—which are often underemphasized in clinical reviews. Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. The number of eligible studies was modest, and many relied on facility-based samples that may overrepresent advanced disease. Heterogeneity in diagnostic criteria across studies also introduces variability in reported prevalence and clinical outcomes. Finally, there is a paucity of longitudinal data, which limits inferences about treatment trajectories and the long-term impact of interventions.

CONCLUSION

Glaucoma in Tanzania remains characterized by high prevalence, low awareness, and late presentation, with systemic barriers compounding the challenge of effective care. Innovative yet pragmatic approaches—such as scaling up selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT), strengthening referral systems, and embedding glaucoma into national eye health strategies—offer realistic opportunities to reduce preventable blindness. Sustained investment in workforce distribution, diagnostic infrastructure, and community-based education will be essential if Tanzania is to shift from reactive to preventive glaucoma care. Aligning these strategies with broader non-communicable disease and vision health policies could help ensure equity, affordability, and long-term sustainability in combating this leading cause of irreversible blindness.

FUNDING STATEMENT

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the administration and colleagues at the Department of Ophthalmology, Temeke Regional Referral Hospital, for their support. We are also grateful to the librarians and information specialists who assisted with the literature search. Finally, we acknowledge the contributions of all the researchers and study participants whose work formed the evidence base for this review.

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :